I grew up during the Cold War, and this past year has felt a lot like it did back in those days; I kept hearing the words “Marxist” and “Socialist” slung around, and occasionally Communist showed up. I didn’t mind. The Cold War years weren’t that bad for me, although they were for many others (Vietnam Vets, thank you for your service).

Of course, most of the time, those words are getting slung around as insults. “Socialist” seems to be the favorite, although Marx comes in for his share of abuse (Incidentally, I predict that the use of “Socialist” is going to change; please stay tuned, especially if you’re Methodist). But where do these words come from, what do they mean and what do we mean by them?

The idea of banning private property isn’t all that new. In fact, long before socialism came about, some Christian groups insisted that everything needed to be owned in common. In modern history, the idea came from the Baptists, or more accurately their ancestors, the Anabaptists, starting in the 16th century. In the 17th century Puritan groups such as the Levelers and the Diggers advocated community ownership of everything. They took literally Jesus’ command to give away everything and follow him.

“Socialism” was born a bit later, in the 18th century. The basic idea was that cooperation was better than competition because excessive competition might destroy humanity. People should group together in communities where production of wealth was done by the whole group. This was all voluntary. Government was not involved. Communities were set up all over the place, including in the United States. Here and there you can still find those kinds of communities. One example is the “kibbutzim” of Israel. While this early socialism was not religious, there were quite a number of religious societies that practiced its approach; the Shakers come to mind.

However, by the early 19th century, a new kind of socialism had been born, one that differed significantly from its immediate ancestors. The newer socialism did involve government action, and its ideals were intended for whole societies, not just for small groups of eccentrics. This wasn’t because socialists loved government (they didn’t), or because they wanted to reduce freedom (they didn’t). Instead, their approach was based on a very straightforward belief: the worker would never get a fair shake.

That simple idea is the foundation of socialism, as well as its sometime-ally, anarchism (that would be a separate column, so I’m not going there today). Socialists believed that the worker would never earn anywhere near the value that he or she produced. The worker would forever have to surrender much of the value of his labor to the property owner. The “capitalist” would always pocket the lion’s share. In other words, it was all about fairness.

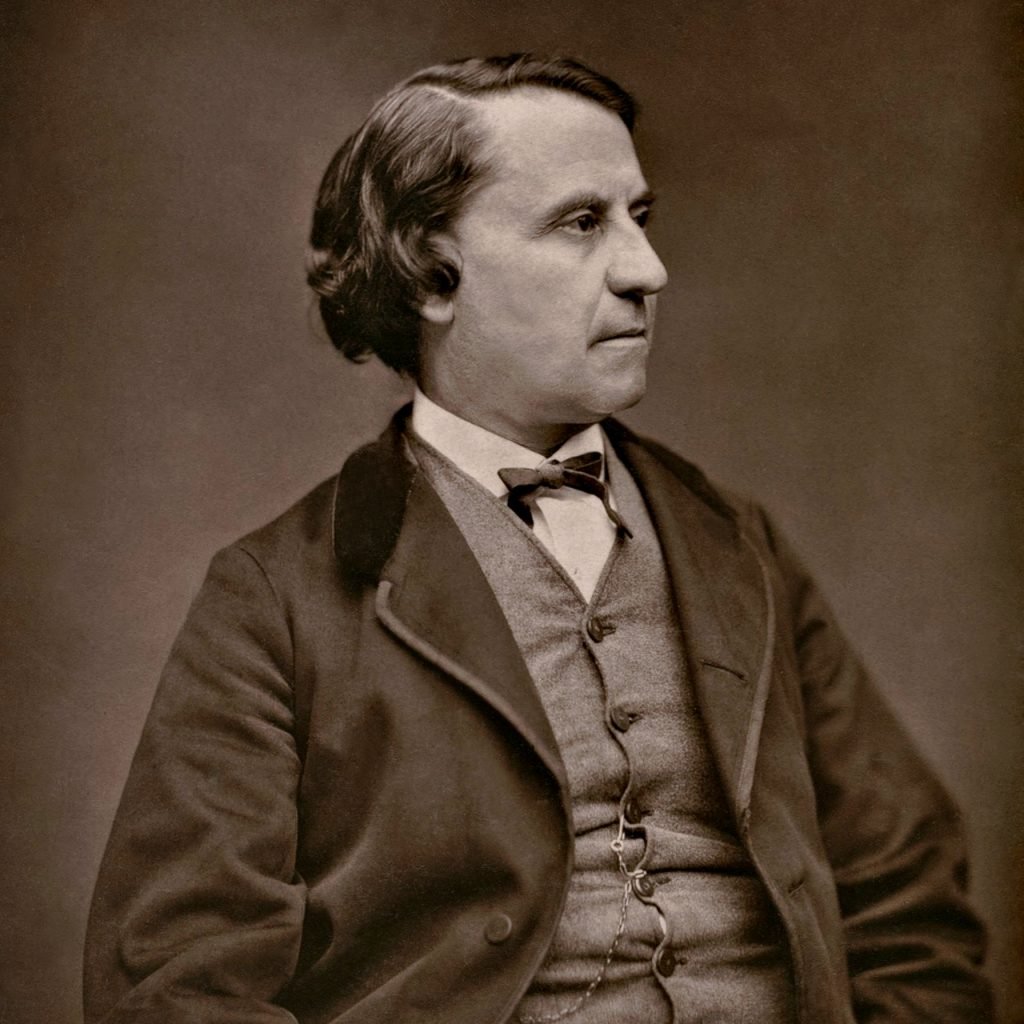

The socialists did not at first demand very radical changes. One of the first great socialists, the Frenchman Louis Blanc, merely pushed for the government to provide work for the mass of destitute unemployed. There were so many of these that if an unskilled worker asked for more money, the employer could easily fire that worker and find another with ease. So, this was just a push to raise the minimum wage.

That project fell apart, and his successors did not see a future in make-work projects. Instead, they moved to what became the conventional definition of socialism: the means of production (factories, mines, etc.) should be owned in common. The people as a whole, not private owners or investors, should control these resources.

Side point: “Socialism” and Hitler’s “National Socialism” have virtually nothing in common, despite the similarity in the names. But that is a whole separate column.

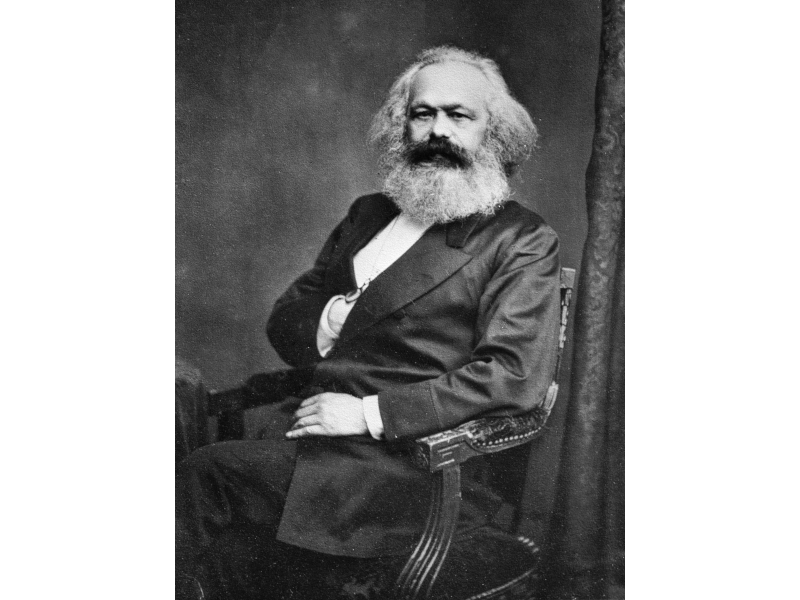

Now here is where it gets really interesting. Socialism generated two very different descendants: Marxism (or Communism) and Social Democracy. Karl Marx was a 19th-century socialist who named his own approach Communism to differentiate itself from other brands of socialism, many of which he despised. In fact, he spent much of his life denouncing the other brands; making friends was not his forte. So, what was the great appeal of Marx, so much so that his writings continue to attract millions of followers, and not a few scholars?

Marx developed a theory of history that postulates society will pass through a series of stages, culminating in the perfect society: Communism, where there is no longer any conflict, and no need for any kind of oppression. There would no longer even be a government. Marx under-girded his perspective with an enormous amount of research and study, which is one reason why his ideas survived as so many others fell by the wayside. The inexorable inevitability of his scheme gave it great popular appeal. Unlike many other socialists, Marx expected a violent revolution (as did the Anarchists, who were otherwise his deadliest enemies).

Most socialists remained outside the Marxist orbit and sought more practical ways of securing improvement in the quality of life. What they came up has been called Social Democracy, and this became the basic political/economic structure in much of Europe, especially after World War II. People and their governments did not want the chaos that had marked the pre-war era, so a compromise was developed. Basically, private enterprise was maintain while a welfare state was developed which guaranteed that citizens’ basic needs were met. European political parties today argue about how big this safety net should be, not whether or not it would exist. The truth is that when we talk about Socialism in America, it’s really Social Democracy that we mean. True socialism, meaning seizing all private production assets, is a fringe movement.

And here’s where we get back to the Methodists.

“Methodism” was originally an insult, aimed at the theology of John Wesley and his followers. They proudly took on the moniker and hence the powerful Methodist movement was born.

I’ve noticed that there are many on the Left who are taking note of their being called Socialist whenever they propose programs to fight poverty or other blemishes on society. They are starting to use the label as a point of pride. Will they be as successful as the Methodists? Only time will tell.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu