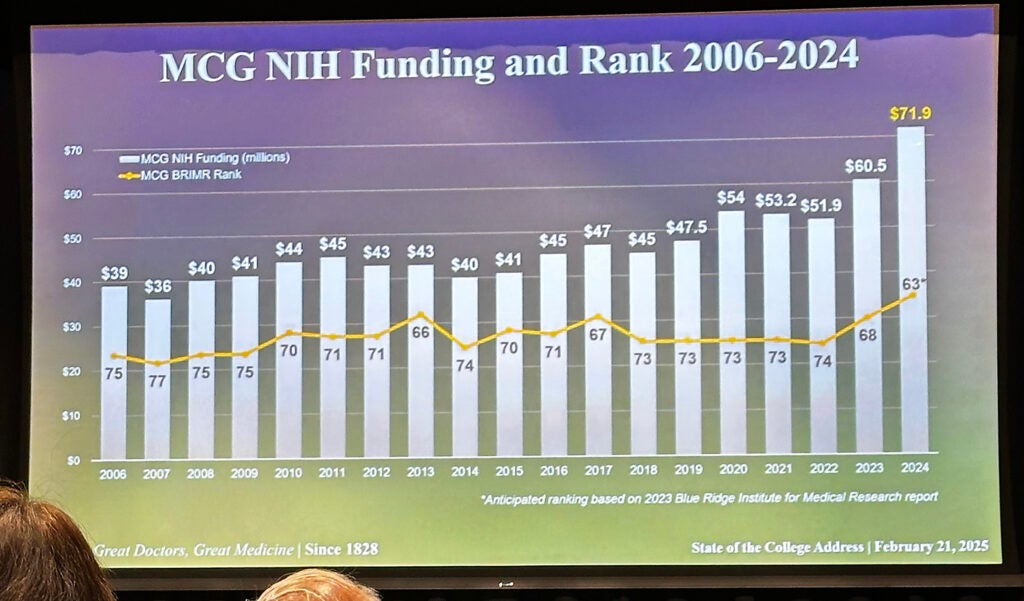

The Medical College of Georgia is growing, with the largest entering class in history and a surge in National Institutes of Health funding. However, looming cuts to NIH funding are a concern, said MCG Dean David Hess in his annual state of the medical college address.

Hess, who filled the speech with employee recognitions and awards and online visits with satellite medical campuses, said MCG relishes its growth in research funding and ranking.

After being “stuck” at about $40-$50 million for years, the college reached more than $70 million in NIH funding last year and awaits its highest-ever Blue Ridge research ranking, he said.

“This is almost a 40% change over the last two years and that’s thanks to you, our faculty, being amazingly productive,” he said. “We also hired more faculty and more researchers thanks to Dr. (Brooks) Keel and now Dr. (Russell) Keen, who have enabled us to do that.”

Georgia ranks in the bottom 10 states for nearly everything medical, and as it attempts to fill a burgeoning physician shortage with medical campuses and training sites around the state, a hospital in Columbia County and a new research building in Augusta, on Feb. 7 it got the notice from NIH to “cap the indirects,” Hess said.

The Trump administration, which vowed to cut $4 billion in medical research funding, signaled it was reducing NIH funding for indirect expenses to 15%.

Augusta’s negotiated indirect cost rate has been 54%, Hess said, “That’s about a 73% drop.” The medical college could lose up to $15 million as a result, he said.

Across the country, Democrat state attorneys general and medical associations filed suit, resulting in a restraining order against the cuts that was extended Friday as a Massachusetts judge completes rulings on a request for an injunction.

NIH funds significant research on life-saving cures and treatments.

“If you look at most of the drugs that have been approved by the FDA in the last 20 years the vast majority have received NIH funding,” Hess said.

Hess said he wasn’t surprised the indirect costs were a target. For non-medical industries, indirect costs are typically lower, at 15% or 20%. “They don’t understand the human-facing industry is highly regulated,” he said.

Caring for animal subjects, humans in clinical trials, pricey drug research and the like is “all very expensive to do and (requires) a lot of overhead,” Hess said.

Across the industry, “everybody is concerned about how to make this up,” he said.

MCG has responded with “a pause on some things” but “no salary cuts” right now.

“We’ll get through this; we just have to be careful,” he said.

Hess said he understood why some members of Congress want to slash wasteful spending, but that’s not NIH funds.

“Nobody thinks of the NIH as wasteful. The NIH is really what differentiates medical research in this country from the rest of the world,” he said.

“Academic medical centers like we are a national treasure and the NIH is a treasure admired by the rest of the world so we don’t want to lose the NIH; we don’t want to lose funding from the NIH,” he said.