People forget that daily life for early colonists in the New World resembled more the lives of those living in the Medieval period rather than what was post-Renaissance Europe.

One great example of this fact is only about three hours away from Augusta and it is totally worthy of a day trip: Fort King George, which was named for George II, not his grandson George III, who lost the colonies in the American Revolution.

MORE: Paine College restores employee benefits

The fort, located in present day Darien, Ga, near the coast and below the border with South Carolina, predates the colony of Georgia, which was established in 1732.

In the years prior to Georgia’s chartering, the land was considered a buffer zone, or “no man’s land.” At that time, the big European powers, France, Spain and Great Britain all had designs on North America, but England was most definitely the dominant player in the game.

A kind of uneasy détente existed among the Europeans, but the British colonists had to contend with the hostile Guale tribe of Native Americans who conducted proxy skirmishes on the part of the Spanish, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

In 1721, Colonel John “Tuscarora Jack” Barnwell, manned and equipped by His Majesty’s Independent Company of Foot, was tasked with building a defensive fortification on the Altamaha River as an inland fort.

However, unlike the castle fortifications of the British countryside, Fort King George was built on the, by then, ancient wood and earthen “motte and bailey” design which consisted of a three-story main structure, or “blockhouse,” on high ground, dependency buildings such as stables, barracks and kitchens on the lower ground that were all protected by a curtain wall and even lower down, a moat with water supplied by the river.

The land they chose was not the optimal site for a fort for the simple reason that it was a defensive position on land that no one wanted to conquer.

Living conditions at Fort King George were spartan at best and even the most robust and healthy of individuals would have a challenging time living that far from civilization in a bug-infested, humid hellhole.

Barnwell had requested of the Crown to be given a squadron of young and able men; however, he ended up with 100 elderly pensioners, many of whom were disabled and barely survived the Atlantic crossing.

It is not known just how many of the men died, some estimate that half the men died within the first year, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, 19 graves have been discovered and preserved.

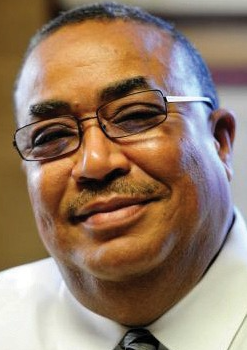

James Cosgrove with Project Past.

None of those buried at the site died of battle wounds, but, rather, it was disease that ravaged the troops.

Not only was the fort almost surrounded by mosquito infested marsh land, but sanitation conditions inside were dreadful as well; with a high water table, the place likely reeked of human and animal waste. Malaria and scurvy were prevalent.

In 1726, a mysterious fire occurred, destroying the blockhouse and several of the barracks. Pretty much all sources label the fire as “mysterious,” because the blockhouse stored gunpowder, so the building had no fireplace, and to protect the blockhouse, fires were not allowed in the barracks either.

By 1732, the fort was abandoned, not necessarily due to the high death rate, but because it was not really needed anymore.

Georgia’s founder James Oglethorpe decided to take a different tactic when dealing with the Spanish’s Native American allies by proposing they trade with the newly arriving settlers. Oglethorpe would oversee the building of several large sawmills and logging became big business in the area near the old fort. Logging would continue for several centuries, with the mills pumping out pine lumber until the 1930s.

Armed with a charter from the king, Oglethorpe brought with him a company of Scottish Highlanders to ostensibly rebuild the fort. However, according to the Georgia Press, Oglethorpe had other plans; rather than build another imposing fortification, he created a trading post that was more inviting to the natives.

With the frontier mostly secure, the next year, Oglethorpe founded Savannah as a major sea port and several years later, in 1736, he raised the flag over his new city of Augusta.

Incidentally, the Garden City’s namesake, HRH Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Princess of Wales, was the mother of George III.

The ramparts of the old fort’s curtain wall were never destroyed and the unique triangular earthen works remained intact, but time and nature eventually took over, making the site a curious relic that few outside the town of Darien knew anything about.

Fort King George would be rediscovered, excavated and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

In 1989, the original blueprints for the fort were discovered in an archive of the British Public Records Office and the main portions of the fort were rebuilt to spec by hand, using the same materials as the colonists did centuries before.

The old fort is now a state park and the authentic cypress and pine blockhouse functions as an educational center that is period correct down to the last detail.

It is still recommended that visitors pack with them a bottle of insect repellant to take the tour; Americans eventually defeated the British, but we can’t seem to beat the mosquito.

…And that is something you may not have known.

By the way, the YouTube channel Project Past has a great video to watch…Check it out here!

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com