For over a century and a half, the Old Medical College building on Telfair Street hid a grisly secret. A renovation of the building in 1989 proved what was always considered a rumor: the medical school once employed the services of a grave robber.

During the renovation of the cellar, workers stumbled across human bones that had been buried in the dirt floor. Fearing they had uncovered a crime scene, the workers called the police.

Once the some 10,000 individual bones were analyzed, they were dated as belonging to people who lived primarily in the 19th century. Historians went to work, and the story of Grandison Harris emerged.

MORE: Something You Might Not Have Known: George Walton

The Medical College of Georgia opened its doors in 1835, and administrators realized they had a problem. How could they teach human anatomy without the dissection of human remains?

At the time, almost no one living were willing to donate their bodies to science for religious reasons. Occasionally, medical schools had access to the bodies of executed criminals and paupers who died with no known kin. However, MCG needed a constant supply of cadavers, so the decision was made to steal the bodies they needed for research and education.

[adrotate banner=”55″]

Seven members of the school’s faculty pooled their money and purchased Grandison Harris at an auction in Charleston. His job on paper was that of a janitor; however, in reality, his job was to provide a constant supply of fresh cadavers.

According to Bess Lovejoy, an editor with Smithsonian Magazine, Harris was taught to read. Even though it was illegal for slaves to be educated at the time. It was so that he could scour the obituaries and determine which body he would steal.

Because Harris was a slave, he was pretty much immune from prosecution for following orders. The college administration went a step farther by having him operate in the Cedar Grove Cemetery, which was a Black cemetery. Because of the racism of the times, robbing the body of a Black person was not considered as serious an offense, at least it was not when compared to stealing a White person’s body.

Harris was apparently very good at his job. According to Lovejoy, he would study the flower arrangement of the fresh grave so that he could put each bouquet back where it had been to avoid suspicion that tampering of the grave had occurred.

MORE: Something You Might Not Have Known: Lost Confederate Gold

Once he dug down to the coffin, Harris would quickly retrieve the corpse and put it in a large sack before refilling the grave and returning the flowers. The body was then transported to MCG where it was placed in a large vat of whiskey for preservation.

According to Lovejoy, some of the bodies would be defleshed for the skeleton to be preserved in the college’s collection. However, most of the bodies had to be disposed of, which led to another problem for administrators. Certainly, the bodies couldn’t be reinterred in their original location, and the smell of a cremation would attract attention. So, instead, the corpses were hacked into smaller pieces and then buried in the basement under a blanket of quicklime that masked the smell.

The fact that MCG had Harris around to fulfill his illegal duties became something of an open secret, especially in the Black community. According to Lovejoy, Harris dressed to the nines and was known to throw lavish parties.

Labeled the “Resurrection Man,” it is not proven, but quite possible that prominent Black folks may have paid Harris for an insurance policy that would allow them to rest in peace instead of ending up in a vat of whiskey.

[adrotate banner=”15″]

Harris performed his work as a slave until the end of the Civil War. For a brief period, Harris moved to the largely Black city of Hamburg, which sat just across the Savannah River from Augusta. During that period of his life, Harris pursued legitimate work and was even appointed as a judge in Hamburg.

However, despite changes to the law that relaxed restrictions on how medical schools could obtain cadavers, MCG found itself once again in need of illegally-obtained corpses.

Harris returned to MCG — this time as a paid employee — and even worked as a teaching assistant. He would continue to rob graves until he retired in 1905, after which Harris’ son George took over his father’s ghoulish job.

Harris died in 1911 and was purportedly buried in his old stomping grounds at Cedar Grove Cemetery. However, according to Historic Augusta Director Eric Montgomery, available records show possible members of Harris’ family, but not of Harris himself.

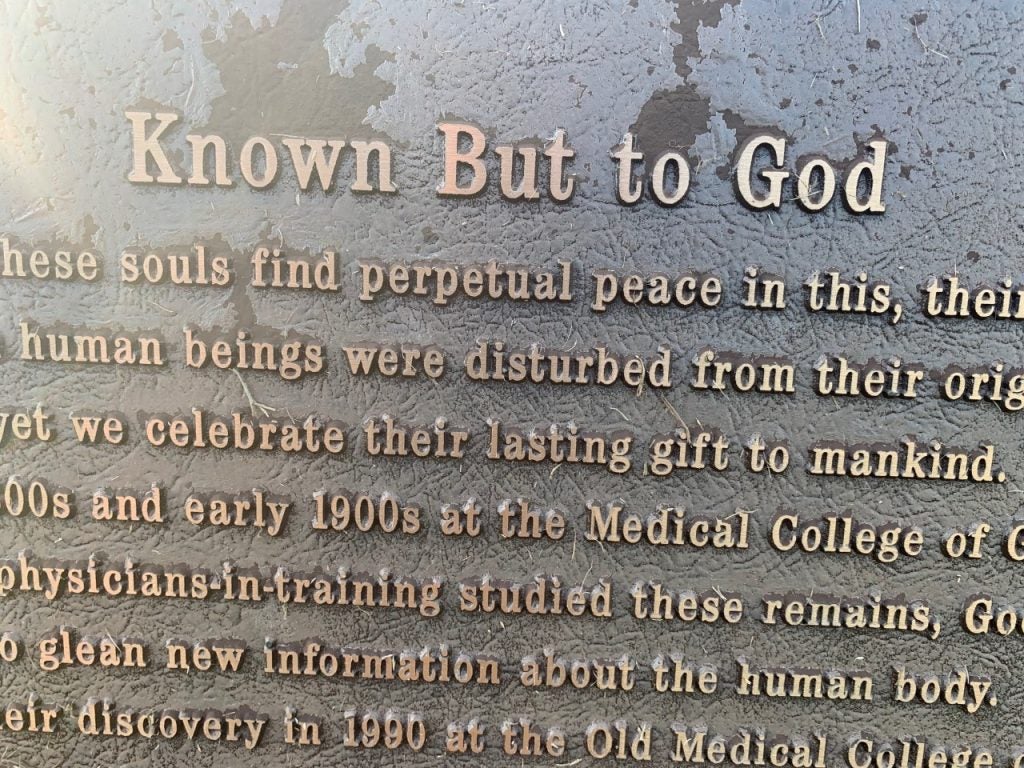

In 1998, the bones in the basement were reinterred together at Cedar Grove. The grave marker plainly states, “Known But to God.”

An afternoon scouring Cedar Grove did not turn up a grave marker for Harris. Perhaps he wanted it that way.

…And that is something you might not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Reporter for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com