As I sub for Scott Hudson this week, I wanted to share one of my most favorite parts of being a journalism historian — reading old newspapers. Settling down with an old newspaper, whether in paper, microfilm or digital form is like stepping into a time machine for me. So, I decided to find the oldest copy of the Augusta Chronicle, our city’s oldest newspaper, and see what was reported in the edition as close to this date as I could get. That ended up being Sept. 22, 1792.

Augusta in 1792

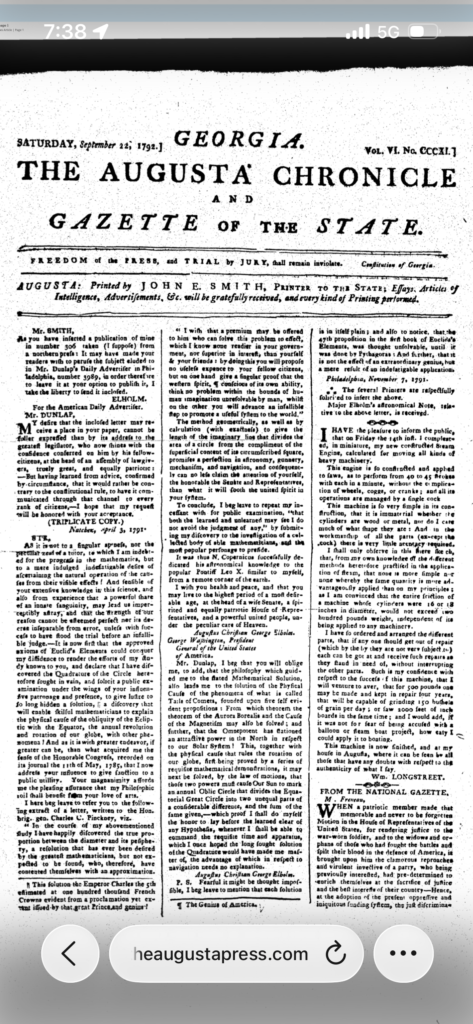

In 1792, the first year for which copies of the Augusta Chronicle remain available, John E. Smith was editor, and the paper carried the motto “Freedom of the Press, and Trial by Jury, shall remain inviolable.” It cited those two rights not to the brand, spanking new U.S. Constitution but the Georgia state Constitution.

As you might imagine, things were different back 223 years ago. The U.S. Constitution was four years old, George Washington was in his first term as president and there were no political parties. Factions, yes. Parties, no.

Not only was government different, so were newspapers, and since I’m sitting in for Scott Hudson for this week’s Something You Might Not Have Known, I thought you might be interested in just how different they were. I’m including PDFs of the Sept. 22, 1792 issue so you can peruse it at your leisure, just like your ancestors did if your family goes back that far in Augusta history and would have had the money to pay for a subscription or even a single copy that week.

Before you start reading, let me point out a few differences between newspapers then and now.

Newspapers in 1792

The masthead at the top of page 1 tells us nothing about John E. Smith other than that he is printer to the state. That means he had the state printing contract, which means he made a pretty good living at his print shop because he printed whatever the state government needed printed. State contracts were fought over because they provided a stable source of funding in a very uncertain world.

You’ll also notice that the mast head solicits contributions. Journalists in those days didn’t go out and gather news. The job of reporter wouldn’t become a reality until the 1830s. Earlier journalists might on rare occasion go out to witness an even and then write about it, but for the most part, they waiting for news to come in the mail, a newspaper someone dropped at the office, a “reliable gentleman” who brought news with him on his visit to town, or correspondence some one in the hinterlands mailed in.

Newspapers also freely copied from one another in a system known as the exchanges — that is, newspapers would agree to send copies to one another to help with the spread of news throughout the country. This is a practice that Congress knew was essential to keeping Americans informed about what was happening in other parts of the country, and so there was no postage charged on exchange newspapers.

The Augusta Chronicle in 1792

The first part of the Chronicle features a letter that a correspondent, Elholm, has sent in. Oh, and note that those letters that look like fs without the crossbars are actually s. “I fuppofe” in the second line means “I suppose.” You’ll see an exchange article in the bottom right-hand of page 1, a reprint from the National Gazette.

Page 1 features a story that likely would be more like to run in an academic journal than in a newspaper today. It’s an explanation of of a mathematical problem related to astronomy. Another page 1 communication is from William Longstreet, who. in 1788, received the first patent for steam engine connected with navigation by water. That patent was issued by the Georgia Legislature; the U.S.Congress, operating under the Articles of Confederation at the time and had no authority to issue patents. Longstreet reported that he had completed a miniature steam engine intended to move heavy machinery. He invited anyone interested to his home in Augusta to see the machine for themselves.

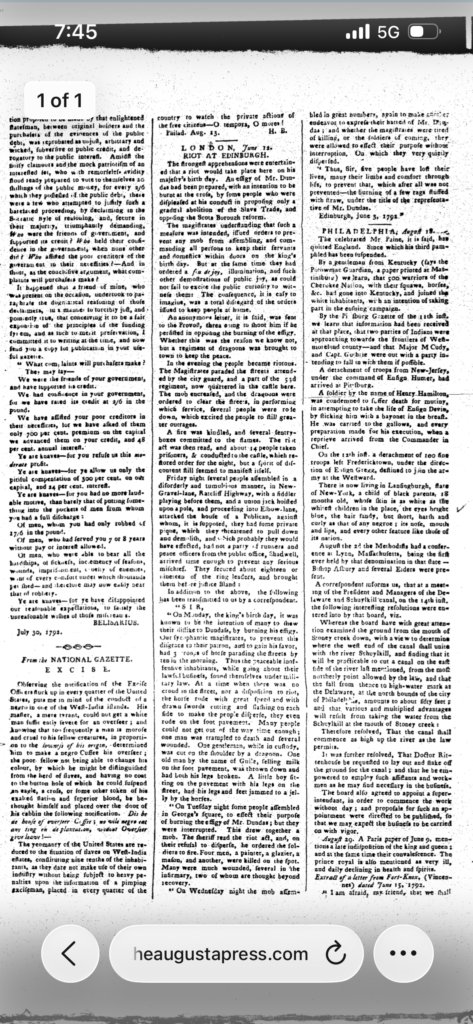

Finally on page 1 was the beginning of a piece about pensions for Revolutionary War soldiers and their widows addressed to Philip Freneau, editor of the National Gazette, which would, as political parties developed over the next few years, become an important supporter of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic Republicans. Freneau, known as the poet of the American Revolution, was also James Madison’s roommate at Princeton University. The piece in the Chronicle was signed Belisarius, likely a pen name, which was common for much writing at the time.

That article continues on page two, and another article from the National Gazette follows. Page 2 also reports on a riot in Edinburgh. It is the closest to a modern day newspaper article since it deals with news — though news that is more than three months old. The rioters burned an effigy of Henry Dundas, a Scottish politician who was serving as the British Home Secretary. Dundas had just amended the legislation to slow down the end slavery in the British empire. His reasons for wanting to slow the abolition of the slave trad were complex – and unpopular with those who preferred a quicker death to the “peculiar institution,” as historians refer to it.

Magistrates tried to stop the mass assembly before it started, but those involved were determined, especially after several of their number were “rode down” by soldiers, according to the article. Eventually, the rioters started a fire and burned several sentry boxes. Some 14 people were arrested, but the crowd still did not disburse. Eventually a fiddler showed up, a Union Jack was hoist, and a pub attacked. Another 18 leaders were arrested and five died, but they succeeded in burning their effigy.

Page two also includes set of news briefs including a story about Thomas Paine leaving England and one of his pamphlets being censored, a report from “a gentleman from Kentucky” that about 500 Cherokees and families had joined white families there to take part of some unnamed campaign, and a similar report from the Pittsburg Gazette about Native Americans joining the military there. The briefs include a story about a soldier named Henry Hamilton who had been sentenced to death for mutiny for attempted murder. He was at the gallows ready to be hanged when a reprieve arrived from President Washington.

Other briefs describe the first ever denominational meeting of Massachusetts Methodists, work on the Delaware and Schuylkill canal, and a story from Paris that the French king and queen were ill.

News continues on page 3, including a shipping report from Norfolk, an obituary for Brig. Gen. Mordecai Gift of Charleston, a solicitation of monetary support for the French people who were fighting the restoration of the monarchy.

One local story invites members of the Mechanical Society to a meeting Thursday at 6 p.m. at John Cook’s place. Members were expected to attend. Military defaulters from Wilkes and Burke counties were also listed in the paper.

Page 4 carried a poem, very common in eighteenth and nineteenth century newspapers, and ads from local merchants and others. D. Robinson & So, a Broad Street dry goods store, announced it had received coffee, a variety of teas, raisins, “prunes in small boxes,” candles, soap, window glass, and other goods, including a variety of alcoholic libations and medicines. A runaway slave ad sought three men, who who was a talented flute player and another who could weld a needle “almost like a woman.” The printing office also offered to exchange paper money for specie at a rate of two-to-one. The paper also announced an estate sale at Washington, Ga., for the estate of John Lindsay, deceased. It included Irish linens and

clothing.

The Augusta Chronicle of 1792 connected Augustans not just to events happening around the country and the world but also exposed them to ideas and scientific advancements in a much different way than newspapers do today. News was anything the editor and readers didn’t already know about, even if it was three months old. Can you imagine living in a time where you don’t have fifty gazillion information inputs coming at you at the speed of light every minute of every day? A time where you’d be glad to read about three-month old riot in far away Edinburgh, Scotland?

It was a different world more than 200 years ago, one I find fascinating and a bit fantastical. On the one hand, I long to visit, and on the other I can’t imagine possibly stepping back that far in time. I’m quite content, I think, to be a spectator 200 years in the future. Please, take a look for yourself, and let me know what you think about spending some time with an old newspaper.

Links:

Part 1 – Page 1

Part 2 – Page 2

Part 3 – Page 3

Part 4 -Page 4