In 1975, Anne Mayer recorded an interview she conducted with Carolyn Dunbar Neville for the Augusta Oral History Project. Neville recounted life in Hephzibah during the earlier half of the 20th century.

“The first people that came to Hephzibah were planters—as they called them in those days,” Neville said, offering a brief history of the founding of Brothersville, the settlement that would become Hephzibah in 1897. Farmers, amid rampant malaria, fled with their families from low land in Burke County.

Neville talks about first moving to the town in the late 1940s or 50s (“25 or 30 years”). She calls it “peaceful and quiet,” and “the greenest, coolest place I ever saw.” She recalls her first trip to the post office there, where she learned that picking up one’s mail was a social event.

“I had the feeling I stepped into a sort of time machine, sometimes,” she said. “I was amazed to find that two of the lovely ladies of Hephzibah had gone to the post office to get their mail, and they were dressed for the occasion. They had on their hats and gloves.”

This would have been close to the founding of the Committee of 100, the development nonprofit that would help kick start further industrialization of Augusta, particularly of its southernmost rural areas.

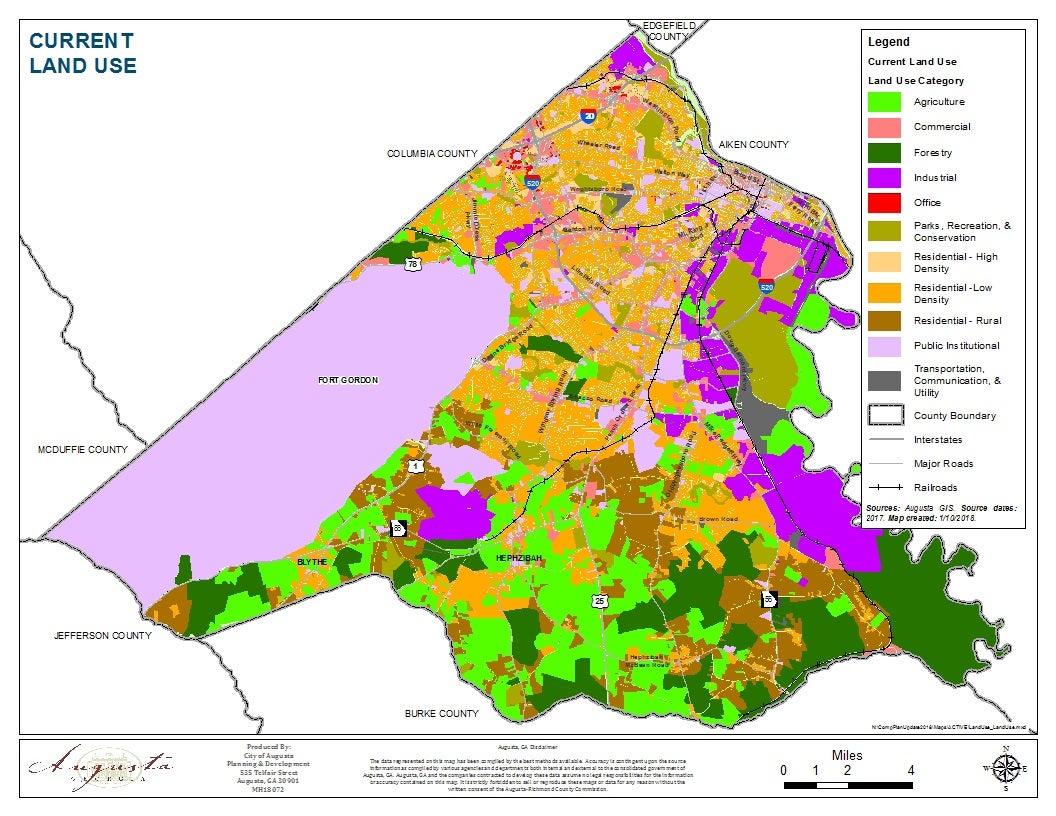

Hephzibah is further south than most of that industrialization, but currently, most of the land close to or below I-520 is still agricultural and rural-residential.

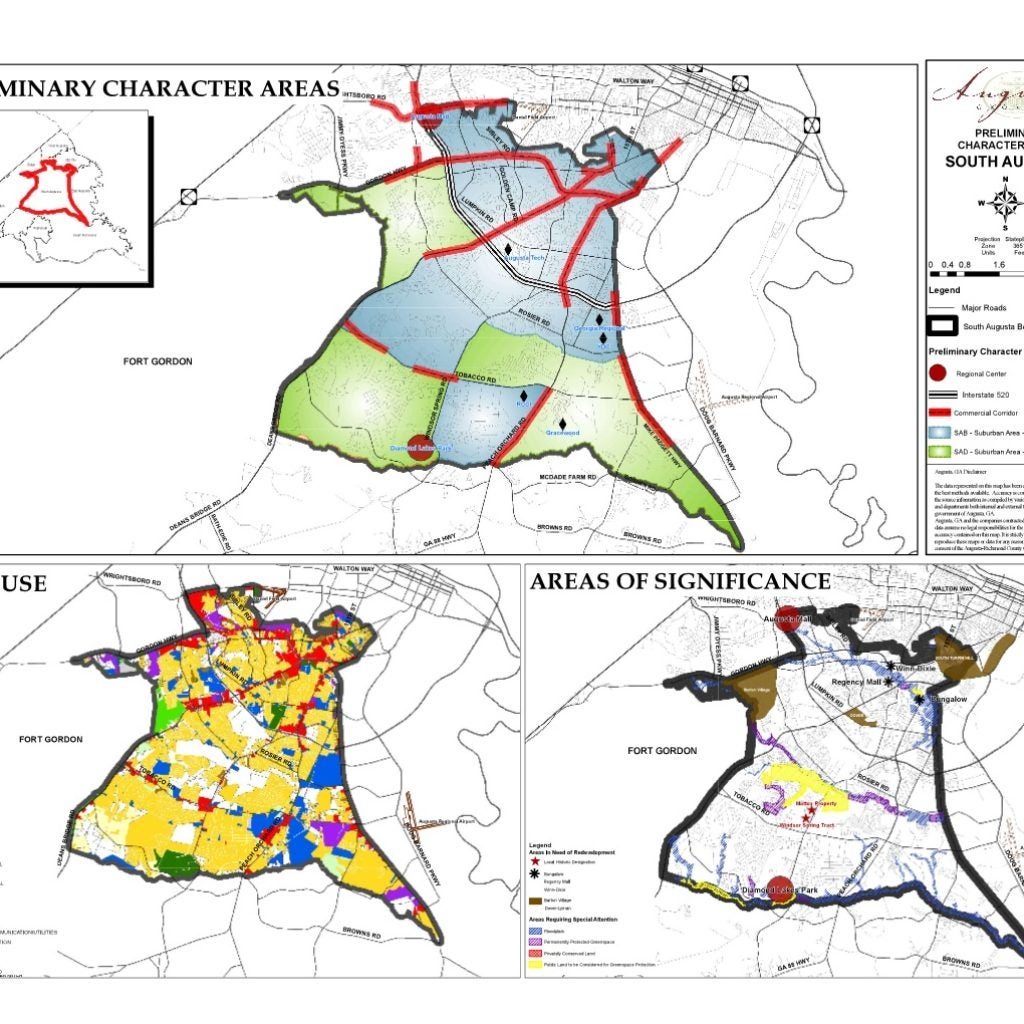

The Augusta 2035 Comprehensive Plan describes the south Augusta area as “largely characterized by a suburban pattern of development,” with subdivision development starting as early as the 1940s. A lot of that development consists of low-density subdivisions of mostly single-family detached units on uniform lots about a fourth of an acre.

The plan refers to the South Richmond Character Area, further south, as “another part of the city undergoing transition,” comprised mostly of open space and agricultural with some rural residential development “characterized by stick-built and manufactures houses on lots exceeding three-quarters-of-an-acre in size,” alongside some burgeoning conventional suburban development.

The document names the Albion Kaolin mine—which was in Hephzibah long before the Committee of 100’s economic development campaigns—as the largest industrial presence in the area, with Augusta Corporate Park, the site of the future PureCycle and Aurubis plants, close behind.

Joyce Law, historian and CSRA representative for the Georgia African-American Historic Preservation Network, notes the development of high-end south Augusta neighborhoods such as the Barefields and Goshen. She said those developments are flourishing amid the area’s rustic sprawl, but also resist its low-end, crime-ridden reputation.

“People living in rural areas, particularly in this day and age, tend to get slighted a little bit,” Law said.

In 1986 (one year after the target projection for the Augusta Planning Commission’s 1968 Master Plan for Land Development), the Augusta City Council Year Book reported more than 3,000 major crimes in the city, including 174 robberies, 310 assaults, and only 10 murders.

The March 1986 murder of 16-year-old Aleta Bunch, after being abducted from the parking lot of the Regency Mall—the beginning of anxieties surrounding the area—was not listed in the yearbook’s major crime summaries.

Skyler Q. Andrews is a staff reporter covering business for The Augusta Press. Reach him at skyler@theaugustapress.com.