Editor’s note: The Rev. Dr. Gaye Williams Morris is the most recent columnist to join The Augusta Press. Morris is a native of Augusta and lives in Manteo, N.C. She is a faculty member of the Department of Communication at Augusta University. She is the affiliated community minister for the Oak Ridge Unitarian Universalist Congregation, Oak Ridge, Tenn. Morris formerly served in ministry at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Augusta. She will be writing monthly on social issues and faith.

I first experienced a Land Acknowledgement at the 2015 Parliament of World Religions in Salt Lake City. All those present were asked to recognize that we were meeting on the traditional, ancestral, unceded territory of the First Nations.

The experience surprised and then overwhelmed me with emotion: how often do we recall the original occupants of this land? How often do clergy call forth the memory of tribal peoples who centuries ago once lived on the present site of their houses of worship? Maybe only once a year, during the Thanksgiving season, when the story of the Pilgrims is recounted.

Yet, we know that native Americans are not just a relic of the past. They live still as Americans today. One vivid reminder of this fact has been happening in Washington, D.C., with the confirmation hearing of Rep. Deb Haaland, D-N.M., nominated by President Biden as Secretary of the Interior.

Rep. Haaland represents New Mexico and is a member of the Laguna Pueblo Native American people. Her confirmation will be historic because not only is she the first Native American to head up a government agency, she will take on the responsibility to administer tribal lands and interests.

Columbus sailed the ocean blue…

In the 1970s, a suggestion was made to rename Columbus Day “Indigenous Peoples Day.” Only a handful of states and cities, including Washington, D.C., and Detroit, have so far renamed the holiday; but recognizing that the slave trade in the western hemisphere, and the genocide of native peoples, result from Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World is the first step to correct the accepted historical narrative, and to hear the lost voices of North America’s indigenous peoples.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is the author of An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2015), which was a Common Read in 2019 for congregations belonging to the Unitarian Universalist Association. Dunbar-Ortiz writes that “today’s indigenous nations and communities are societies formed by their resistance to colonialism, through which they have carried their practices and histories. It is breathtaking, but no miracle, that they have survived as peoples.”

[adrotate banner=”19″]

There’s a lot wrong with the original Columbus Day federal holiday, which was created in 1937 by President Roosevelt, bowing to the desire by Catholic Italian-Americans who wanted Columbus to be included in American history: Columbus did not actually land where the United States is geographically located today, but once he landed, his crew’s treatment of the native population of Hispaniola was not very Christian! Friar Bartolome de Las Casas, a Spanish colonist and scholar, wrote of the brutal treatment of the native men, women, and children of the Taino population.

People of faith are beginning to appreciate the scale of oppression in this country that has resulted from the doctrine of discovery originating in Papal Bulls over 500 years ago.

The High School Pledge of Allegiance story

I had my own discovery, as a young girl, that my dad was adopted, and that his mother was a Native American, so I actually had a Native American grandmother. She died when I was about 6, and although I have seen photos of being held by her as a baby, I don’t recall ever meeting her.

And as a rebellious teenager, I began reading Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and God is Red, and as I learned more, I felt tremendous solidarity with Native American tribes who were forced to hand over their lands and live on reservations…so much so that, in high school, I refused to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance out of a sense of outrage. I realized there was not liberty and justice for all; I felt that in my heart, just as I felt helpless to do anything about it except demonstrate that solidarity in an act of rebellion, which got me disqualified by the principal from running for president of student council!

As an adult I’ve learned more about the “traditional, ancestral, unceded territory of the First Nations” mentioned in the Land Acknowledgement.

I learned that this territory was not a wilderness, and it was not a New World. The artist John White who came with the English colonists made numerous illustrations of the towns and settlements of the natives, who gave help to the colonists arriving in North Carolina, Massachusetts and Virginia. They had much to offer with their domesticated agricultural societies of hunting, fishing, farming and gathering.

Rethinking the accepted national narrative about indigenous peoples means that we recognize that, among other things, they had sovereign self-governing systems, their own languages, belief systems and rituals, monumental earthworks, farms, transportation systems, trails and roads.

Indigenous peoples were not prehistoric savages – this was a ‘continent of nations’ – but the still-powerful ideological devotion to manifest destiny and the European culture of conquest makes us blind to the lives of peoples snuffed out, enslaved and constrained in the centuries since the Europeans arrived.

The indigenous peoples of this continent were not the first to experience European colonization and extermination – the Crusades from the 11th to the 13th centuries in North Africa and the Middle East were driven as much by the profit motive in controlling Muslim trade routes as by Christian zeal to kill the infidels, according to Dunbar-Ortiz.

The rationale of conquest was fueled by the Calvinist theological belief that the escape of the New England colonists from religious persecution in Europe echoed the escape from slavery of the Israelites, called by and covenanted with God to find their Promised Land. Dunbar-Ortiz writes that the key moment in history, according to covenant ideology, “involved the winning of The Land from alien, and indeed, evil forces.”

She claims that what has followed from that is the narrative that America is a “nation of immigrants”…but what that really means is that from the beginning, the United States has welcomed – indeed, often solicited, even bribed – immigrants to repopulate conquered territories ‘cleansed’ of their indigenous inhabitants.”(51)

[adrotate banner=”20″]

Cleaning up the crime scene…

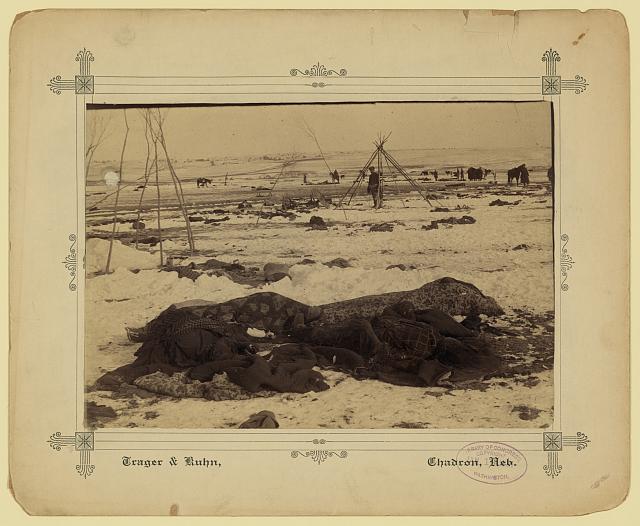

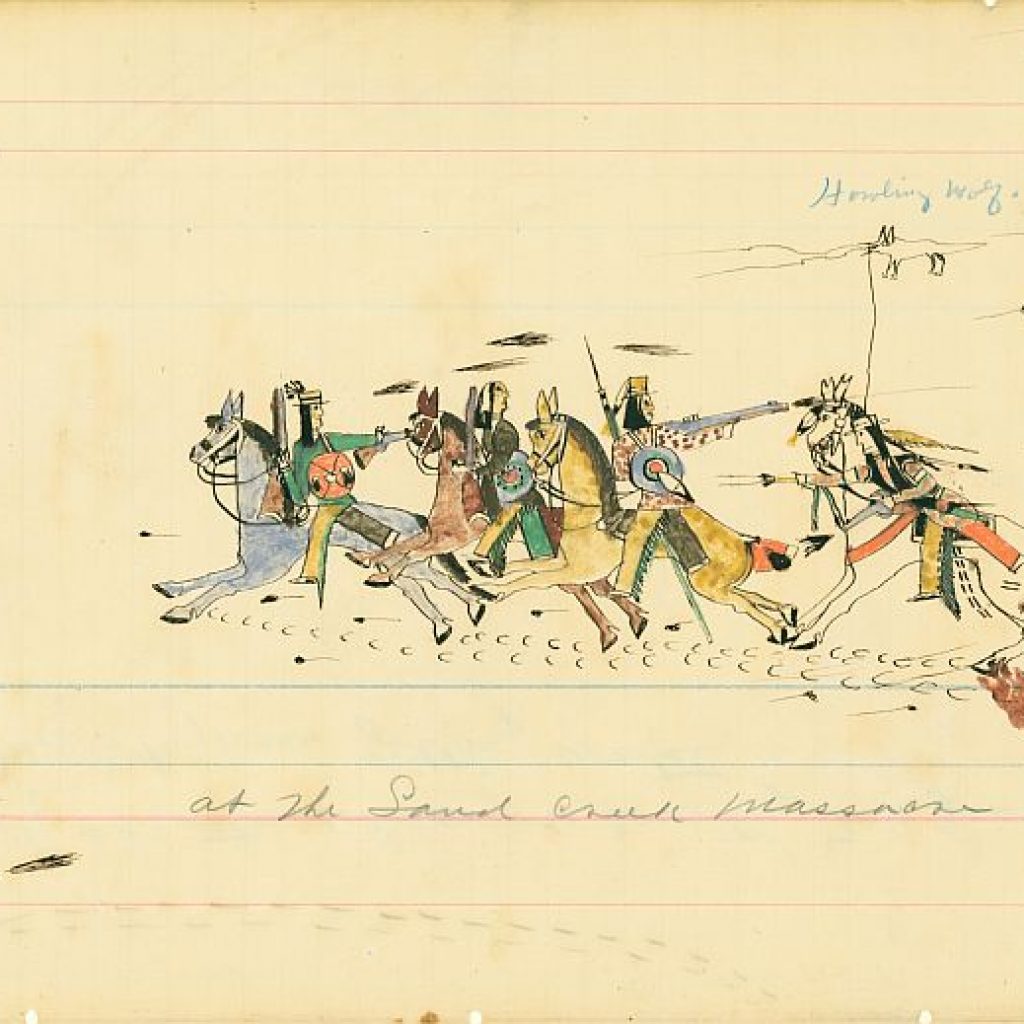

After the US military’s massacre of Lakota men, women and children at Wounded Knee in December of 1890, many white people did indeed call for the total extermination of native Americans…including one who said, “Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth.” This quote was reprinted in David Treuer’s The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee (Riverhead Books, 2019). That person Treuer quoted was Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

In his 1963 book Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King Jr. observed, “Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race… We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or feel remorse for this shameful episode.”

Dunbar-Ortiz says that North America is a crime scene. Why can’t we see that? We as a nation are blind to what was done to the peoples who lived here before the European invasion of this land. And we often speak as though it was a “New World’ with no reference to its original inhabitants. Dunbar-Ortiz mentions how the media described the Virginia Tech mass shooting in April 2007: “the worst mass killing,” “the worst massacre” in US history. Clearly not, and “descendants of massacred indigenous ancestors took exception to that designation.”

Thankfully, there is a slow but steady rise in consciousness on this continent and across the globe as to the need for establishing right relations with the indigenous peoples of the world. The connection with the land and the right of native peoples to their territories in this country have come up against corporate energy interests in court cases and protests for decades. Our country’s tribal lands have been the focus of resistance, and now some interesting alliances are being made.

Last year, teenage climate advocate Greta Thunberg was honored by Sioux leaders at Standing Rock in North Dakota, the scene of fierce environmental protests in 2017, and given a native name that translates as “woman who came from the heavens.”

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted ten years earlier, in 2007, asking UN member nations to negotiate, in full faith and with honor and mutuality, right relationship with the indigenous peoples among them.

People of faith can also act in our own way to eliminate the impact of the Doctrine of Discovery upon theologies and policies, programs and structures of our religious institutions.

Unitarian Universalist minister Michael Tino writes in a piece, “Looking Back to Look Forward”: “We as people can seek right relationship with the indigenous people of this land and with our common mother, the Earth. Do you know whose ancient territory you sit upon…? If not, find out. Find out where those people are today. Seek healing with honor and openness.” (Michael Tino, “Looking Back to Look Forward,”

May this be our task going forward.

Gaye Morris is a columnist for The Augusta Press.

[adrotate banner=”22″]