Modern Olympic Games don’t always go smoothly.

Horrific events such as the kidnapping and murder of athletes in Munich in 1972 and the bombing in Atlanta in 1996 have occurred. Political upheaval has marred the Games as have other controversies. The 2020 Tokyo Games, which will be held July 23-Aug. 8, are not immune. COVID-19 has been a top concern.

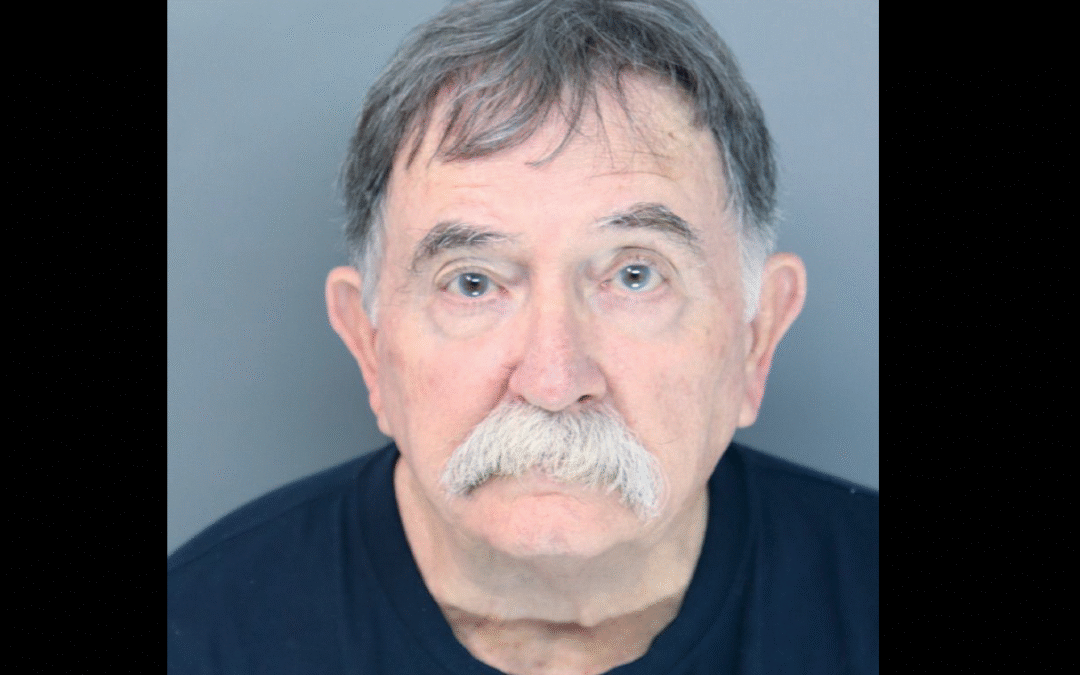

Dacre Stoker knows first-hand what it’s like to be part of an Olympic controversy.

MORE: Former Washington County Star Heading to 2021 Olympics

As a Canadian college student, Stoker, an author and lecturer who has lived in Aiken for more than 25 years, was part of the Canadian Pentathlon team in 1980 — the year the U.S., Canadians and others boycotted the Games in Moscow in protest to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

Stoker’s journey to the Olympic team began four years before at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, where Stoker was born.

[adrotate banner=”54″]

“I was an equestrian growing up,” said Stoker.

Stoker’s father, Desmond Stoker, was instrumental in implementing drug testing for horses. He was also part of the Canadian Equestrian Team Committee in the 1970s. In 1976, Desmond Stoker was in charge of the drug testing of horses for the Montreal Olympics.

And almost by default, Dacre Stoker and his two sisters, Tara Bostwick and Deirdre Stoker Vaillancourt, assisted in banding the horses’ ankles after Olympic events and escorting the animals for drug tests. Deirdre Vaillancourt is married to Michel Vaillancourt, who won a silver medal in Montreal in show jumping.

That environment piqued Stoker’s interest, and he decided then that he wanted to qualify for the 1980 Olympics. Already an accomplished horseman, Stoker eyed the pentathlon with its five different sports of riding, shooting, swimming, running and fencing.

[adrotate banner=”19″]

A student at St. Lawrence University, Stoker got involved with the college’s swim and cross-country teams, he found fencing and shooting clubs and threw himself into the sport.

Stoker said he wasn’t the best swimmer when he started, but he ended up becoming the university’s swim team captain.

In January 1980, Stoker headed to San Antonio, Texas, where he and other Canadian athletes trained together with the Americans.

The Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan on Christmas Eve 1979.

Stoker remembers officials debating what to do.

“The only thing we could do was train,” he said. “Our fate was in the hands of our national governing bodies.”

Stoker also recalls having an internal struggle. He said he wanted to compete because of all the time and effort he’d put into it. At the same time, he was morally torn and felt he was being selfish when considering the fate of the Afghani people.

[adrotate banner=”29″]

In late April 1980, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau announced his nation would support the boycott.

Stoker said the Canadian athletes picked up and headed home. He spent the next week partying and found a summer job. The following year, he finished college and got a job teaching and coaching. He tried to train, but it was too much with the full-time job. He knew that his career as a participant in the sport was over, but he went on to coaching athletes.

In 1988, Stoker made it to the Olympics in Seoul, South Korea as the coach for the Canadian Pentathlon Team.

“We had our best finish ever — 11th out of 22 teams,” he said.

MORE: Local Swimmer Competes Among the Nation’s Best

He remembered the excitement of the event, the camaraderie among the athletes in the Olympic village and the opening ceremonies.

It all floods back whenever the Games are played.

Stoker’s last Olympic experience came as a spectator at the 1996 Atlanta Games, where he was able to reconnect with some of his friends from the sport years before.

And as he watches the Tokyo Games, he’ll do something that has become a tradition.

“I’ll wear my Olympic ring for the 3½ weeks of the Games,” he said.

Charmain Z. Brackett is the Features Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach her at charmain@theaugustapress.com.

[adrotate banner=”56″]