Augusta is a monument rich city; one of the must-dos for tourists coming into town is to snap a photo with the statue of James Brown.

However, there is one monument that is off limits to the public, and that is the tall statue of Patrick Walsh.

Walsh was born in 1840 in Ballingarry in County Limerick, Ireland. He is still celebrated in that country as the only man from Limerick to become a U.S. senator.

When Walsh was but a lad of eight years, the Irish Potato Famine, or Great Hunger, swept through Ireland leaving at least a million dead of starvation. The famine also kicked off a mass migration to the New World, and Walsh’s family was among those determined to brave the ocean blue for a new life in America.

The Irish immigrants didn’t have the easiest of times settling into their new land as stereotypes quickly arose that labeled them as a bunch of red-haired, lazy drunks. Irish men were derisively called “Mickey” and Irish women, many of whom found work as domestics, got used to being called “Maggie” as opposed to their given names.

MORE: Sheriff spends on jail upgrades, committee may look at systemic jail issues

Walsh, however, didn’t seem to have much of a problem assimilating into American society. Settling in Charleston, S.C., he took up an apprenticeship and eventually became a paid printer and typographer. During this time, Walsh saved his money to put himself through night school and eventually graduated from Georgetown University.

No sooner than Walsh received his diploma, the Civil War began and, at first, he enlisted.

However, according to Irish Central, Walsh was a man of words, not weapons and soon resigned his post using his elderly and ailing parents as an excuse.

Being an immigrant and part of a group considered second class in America, Walsh wasn’t exactly on board with the aims of the Confederacy.

Upon returning to Charleston, Walsh became involved in local politics and joined the Charleston Typographers’ Union.

In 1862, Walsh moved to Augusta and became an editor with The Augusta Constitutionalist newspaper, which was eventually bought by The Augusta Chronicle. During this time, Walsh also served as the treasurer and general manager of the Southern Press Association, according to Irish Central, which hails him as “the heartbeat of the Southern press.”

After the war, Walsh used his press stature to lobby for reconciliation and rebuilding the economy. An anti-segregationist, Walsh decried the poor treatment of former slaves and urged the citizenry to unite behind building a new South.

With the political bug still biting at him, Walsh ran for and won a seat in the Georgia General Assembly in 1872 and was later tapped by the Georgia governor, in 1894, to fill an unexpired term in the United States Senate.

After his stint in Washington, D.C., Walsh returned to Augusta and was elected mayor of Augusta in 1897. During his tenure, Walsh again showed his anti-segregationist leanings. When the governor of North Carolina refused to allow a regiment of Black men to set up a base in the state capital, Walsh invited the men to relocate their base to Augusta, which they did.

Due to his easy-going manner and glib tongue, Walsh quickly became probably one of the most beloved mayors that Augusta has ever had. However, it did not last very long. In 1899, Walsh died unexpectedly at age 59, plunging the entire city into mourning.

According to historian Doug Herman, Walsh received two funerals at two different churches and a throng of thousands accompanied his remains in a solemn march to Magnolia Cemetery where he was buried beneath a simple limestone cross.

After his death, Walsh was still beloved by the citizens of his adopted hometown. In 1902, the Augusta chapter of the Knights of Columbus was named in his honor, and in 1913, a giant statue and memorial was erected in his honor on Telfair Street.

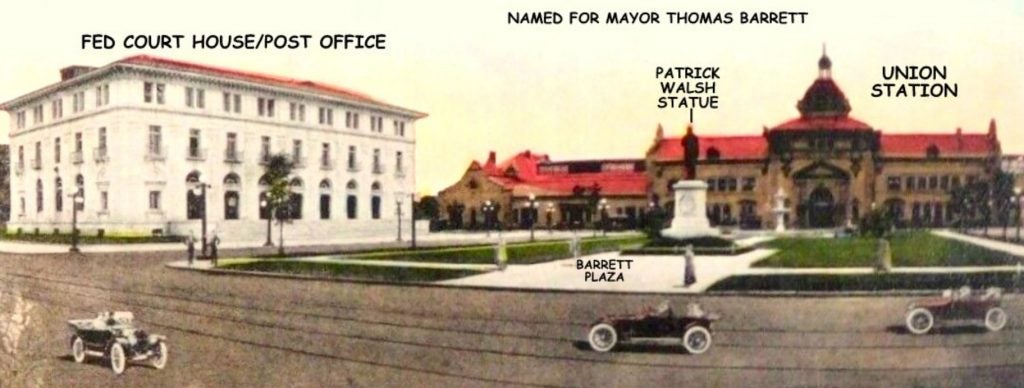

City leaders found the most prominent place in town to erect Walsh’s monument; it was placed on the lawn heading towards the entranceway of Union Station.

Sadly, Union Station was demolished in 1974 to make way for the Post Office and Federal Justice Center. After the terror attacks of September 2001, the federal courthouse was secured with a high wrought iron fence and access to the quad is only allowed to those with business before the court. A brick wall obscures most of the monument from the street.

Herman says it is sad that everyday citizens cannot have access to view the full monument.

“I’ve called and left messages, but have never gotten a response from them,” Herman said.

…And that is something you might not have known.

Scott Hudson is the senior reporter for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com